ادبیات نظری گذار به دموکراسی نشان میدهد که تغییرات سیاسی پایدار، نه صرفاً محصول جابهجایی قدرت، بلکه نتیجه شکلگیری نهادهای پایدار، فرهنگ سیاسی مبتنی بر مدارا، و توافق بر اصول بنیادین حقوق بشر است. تجربه کشورهای مختلف در نیمقرن گذشته نیز مؤید آن است که گذار موفق زمانی رخ میدهد که نیروهای اجتماعی بتوانند میان رقابت سیاسی و تعهد به قواعد مشترک تمایز قائل شوند.

در این چارچوب، جنبش دانشجویی ایران را باید فراتر از یک کنشگر مقطعی در نظر گرفت. این جنبش، در طول تاریخ معاصر، همواره بخشی از نیروی محرکه جامعه مدنی بوده و در بزنگاههای تاریخی، نقشی تعیینکننده در طرح گفتمان آزادی، عدالت و قانونگرایی ایفا کرده است. اهمیت جنبش دانشجویی نه فقط در مطالبهگری، بلکه در ظرفیت آن برای بازتعریف افقهای سیاسی و اخلاقی جامعه نهفته است.

در شرایط کنونی، که جامعه ایران با مجموعهای از بحرانهای ساختاری، کاهش اعتماد عمومی و شکافهای سیاسی و اجتماعی مواجه است، مسئله اصلی دیگر صرفاً «چه کسی حکومت خواهد کرد» نیست؛ بلکه این پرسش بنیادین مطرح است که آیا زیرساختهای دموکراتیک، سازوکارهای تضمینکننده حقوق برابر، و فرهنگ سیاسی مبتنی بر تکثر شکل خواهند گرفت یا خیر.

بیانیه مشترک جبهه متحد دانشجویی و جبهه دموکراتیک ایران را باید در همین چارچوب نظری تحلیل کرد. این بیانیه صرفاً اعلام حمایت از یک فراخوان نیست؛ بلکه تأکیدی است بر تقدم نهادسازی دموکراتیک بر رقابتهای قدرتمحور. تأکید بر حقوق بنیادین شهروندی، پایبندی به روشهای مدنی و مسالمتآمیز، و ضرورت حاکمیت قانون، نشاندهنده درکی نهادمحور از فرایند گذار است.

در تجربههای گذار ناموفق، فقدان توافق بر اصول بنیادین، شخصیسازی سیاست و حذف تکثر اجتماعی، زمینهساز بازتولید اقتدارگرایی شده است. در مقابل، تجربههای موفق نشان دادهاند که توافق حداقلی بر اصولی چون حقوق بشر، برابری در برابر قانون، آزادی بیان و مشارکت سیاسی، شرط لازم برای تثبیت نظم دموکراتیک است.

Student Message Press بر این باور است که نقش رسانه مستقل، فراتر از بازتاب رویدادهاست؛ این رسانه خود را متعهد به تقویت گفتمان حقوقمحور، نهادگرایانه و مبتنی بر مسئولیت مدنی میداند. انتشار این بیانیه در همین راستا صورت میگیرد: بهعنوان سندی در حمایت از کنش مدنی مسئولانه و تأکید بر ضرورت طراحی نهادی آینده ایران بر پایه اصول جهانشمول حقوق بشر.

در ادامه، متن کامل بیانیه منتشر میشود.

🌿🌸🌼🌷🌿🌸🌼🌷🌿🌹🍀🌺☘️🌼🌱🌸🌿🌷☘️🌺🍃🌼🌿🌸

بیانیه مشترک

حمایت جبهه متحد دانشجویی و جبهه دموکراتیک ایران از فراخوانهای دانشجویان

۲۷ بهمن ۱۴۰۴

تهران

جبهه متحد دانشجویی و جبهه دموکراتیک ایران با صدور این بیانیه، حمایت رسمی خود را از فراخوانهای اخیر دانشجویان اعلام میدارند.

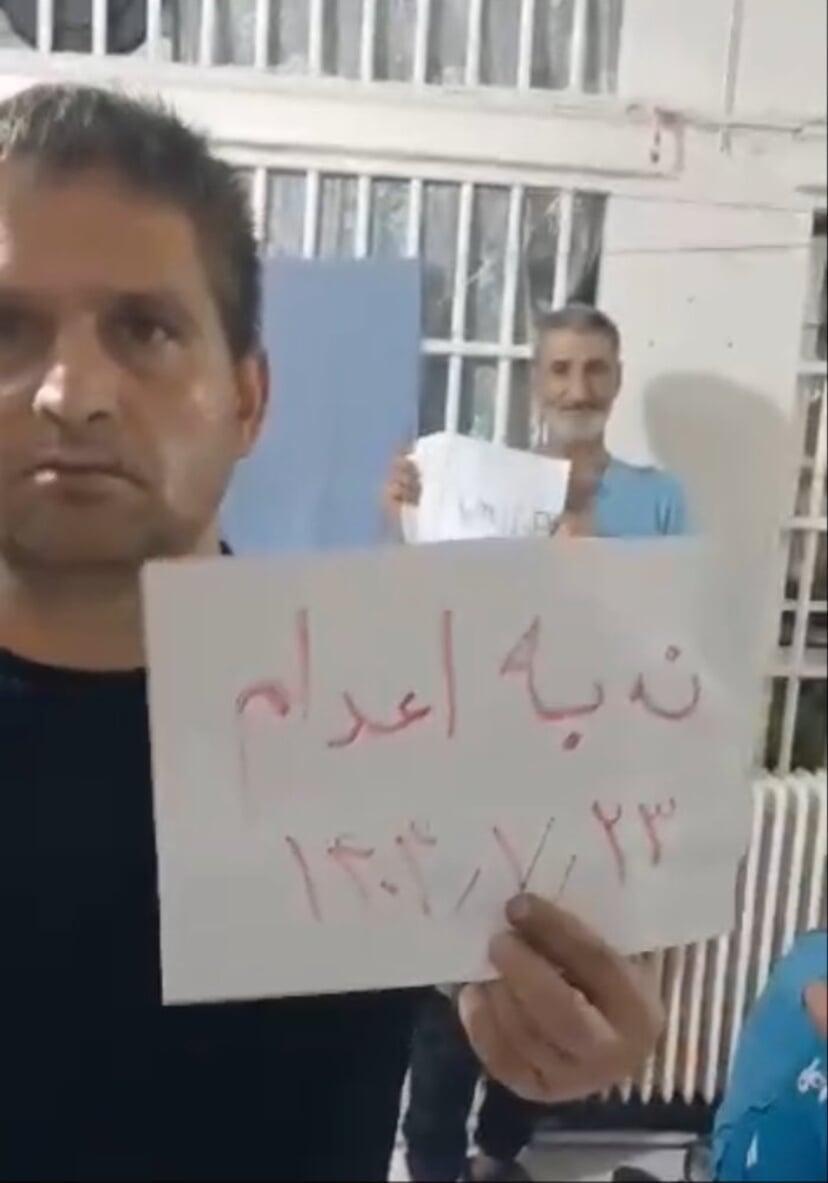

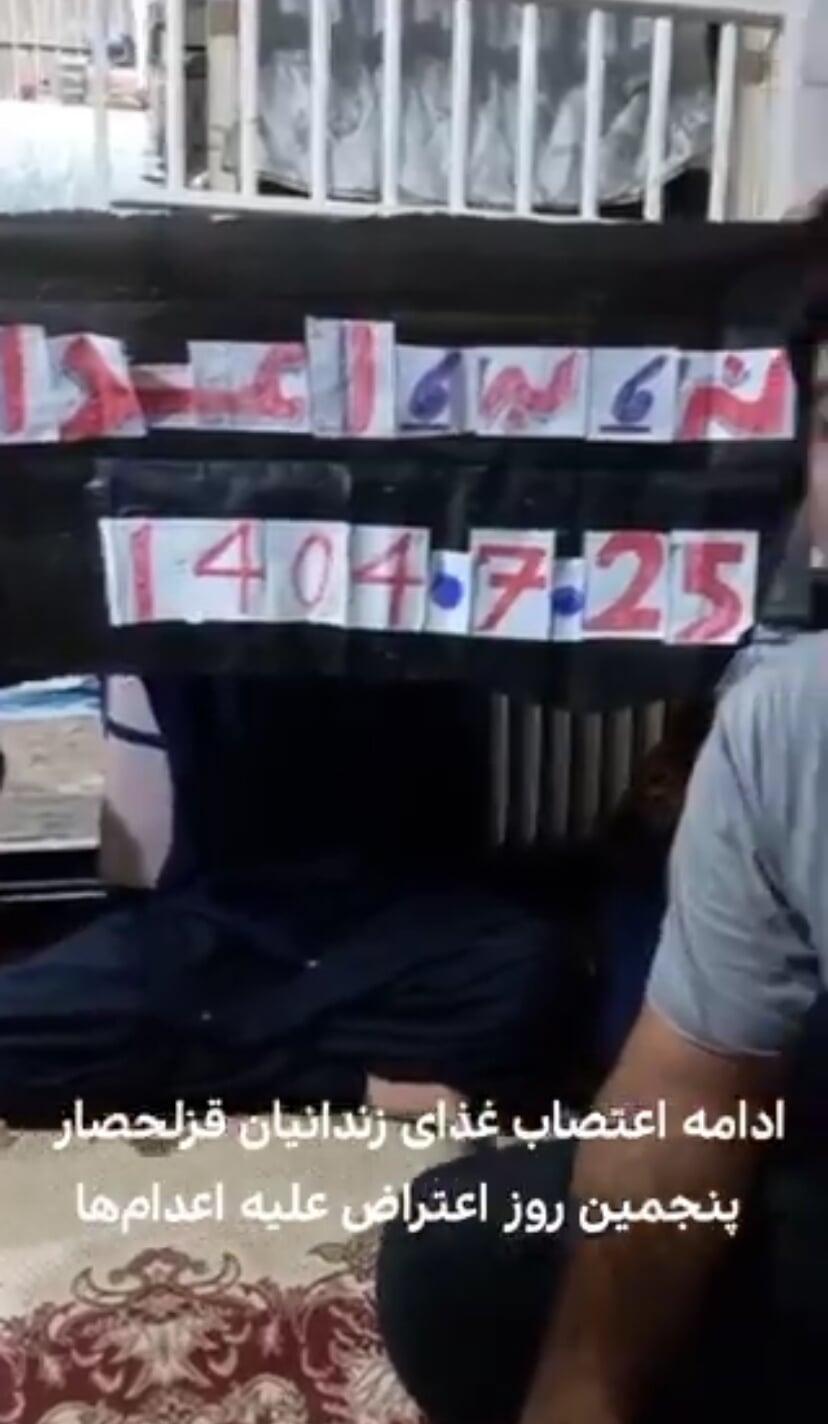

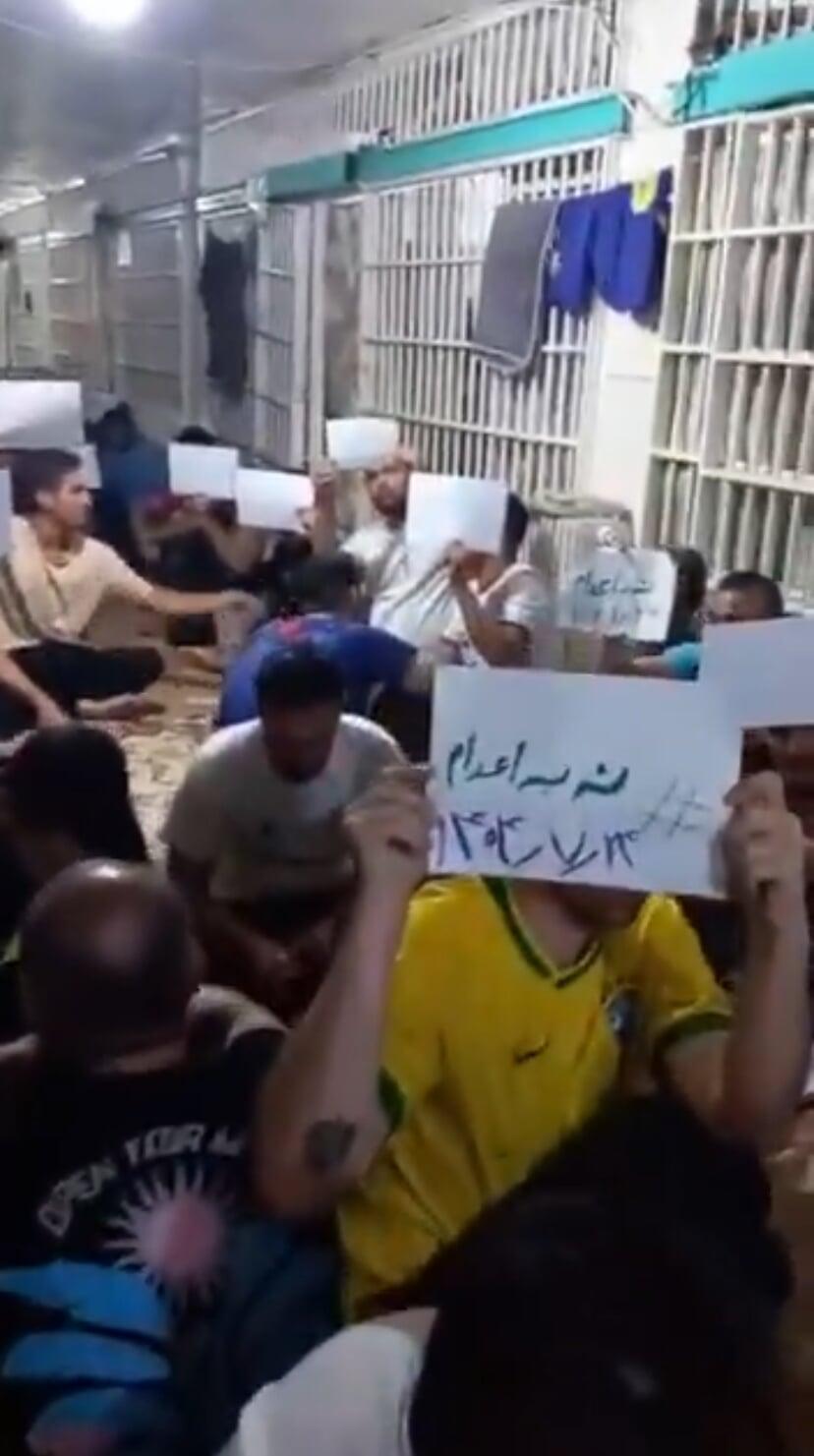

جنبش دانشجویی در ایران، در طول دهههای گذشته، همواره یکی از ارکان پویا و تأثیرگذار جامعه مدنی بوده و در مقاطع مختلف تاریخی، نقش مهمی در طرح مطالبات آزادیخواهانه، عدالتطلبانه و قانونمدارانه ایفا کرده است. بر این اساس، مطالبات دانشجویان در چارچوب حقوق بنیادین شهروندی—از جمله آزادی بیان، آزادی تشکلیابی مستقل، حق تجمع مسالمتآمیز و مشارکت مدنی—از مشروعیت کامل برخوردار است.

ما تأکید میکنیم که پیگیری این مطالبات باید بر پایه اصول دموکراتیک، حاکمیت قانون و موازین شناختهشده جهانی حقوق بشر صورت گیرد. تقویت فرهنگ گفتوگو، پذیرش تکثر سیاسی، اجتماعی و فرهنگی، و بهرسمیتشناختن حقوق برابر تمامی شهروندان، پیششرطهای اساسی هرگونه تحول پایدار و عادلانه در کشور است.

در شرایط کنونی که جامعه ایران با چالشهای پیچیده سیاسی، اقتصادی و اجتماعی روبهروست، مسئولیت نیروهای مدنی و سیاسی آن است که از مطالبات قانونی و مسالمتآمیز دانشجویان حمایت کرده و از هرگونه رویکرد تنشزا، حذفگرایانه یا خشونتآمیز پرهیز شود. مسیر اصلاح و گذار به حکمرانی دموکراتیک تنها از طریق تقویت نهادهای مدنی، گسترش مشارکت آگاهانه شهروندان و تضمین عملی آزادیهای اساسی هموار خواهد شد.

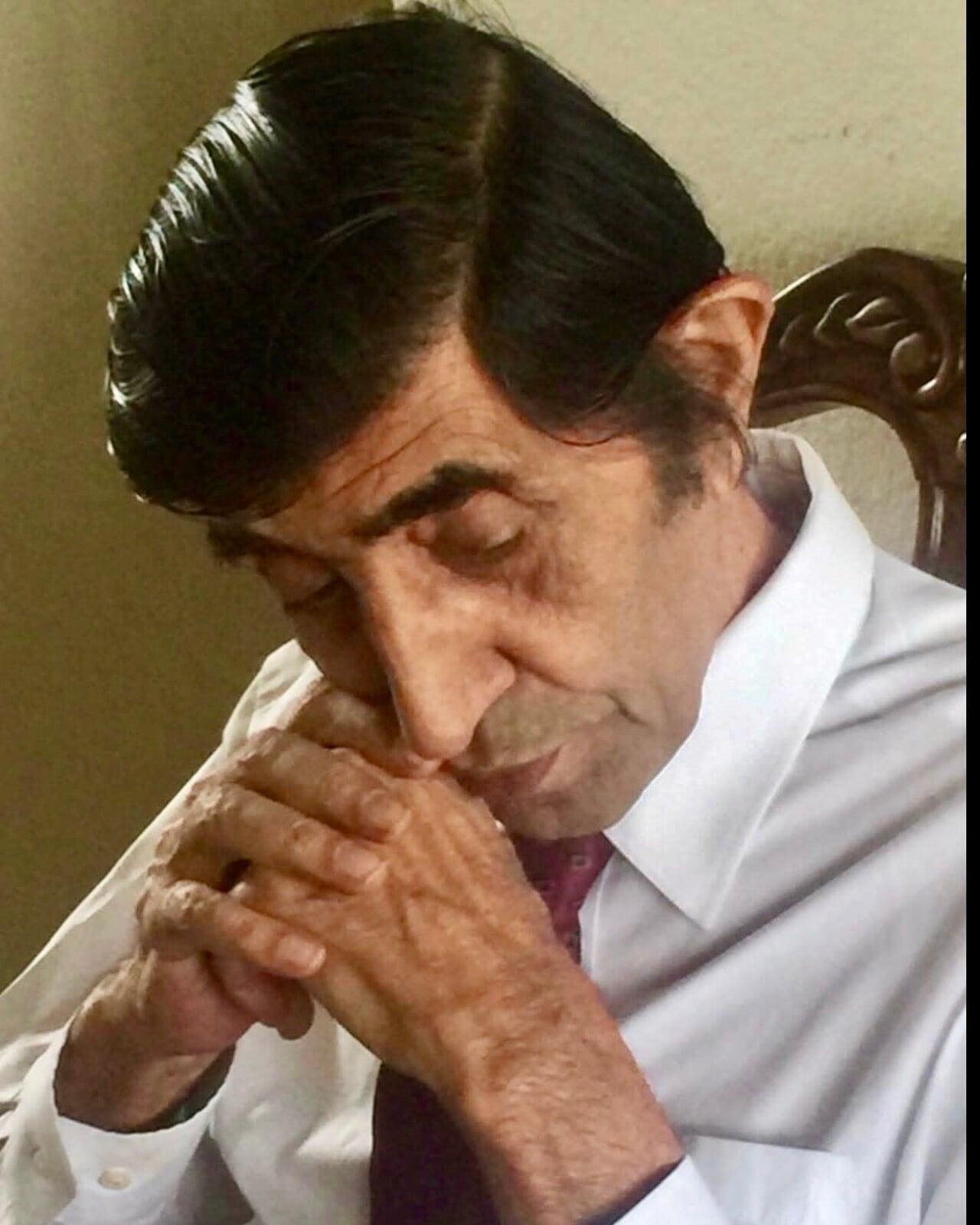

حشمت اله طبرزدی، دبیرکل جبهه دموکراتیک ایران، در این چارچوب بر ضرورت همبستگی نیروهای مدنی و سیاسی در دفاع از حقوق بنیادین شهروندان تأکید کرده و حمایت خود را از مطالبات قانونی و مسالمتآمیز دانشجویان اعلام میکند. وی استقرار نهادهای دموکراتیک، تضمین حقوق برابر و پایبندی عملی به اصول جهانی حقوق بشر را لازمه شکلگیری آیندهای باثبات، عادلانه و توسعهمحور برای ایران دانسته است.

جبهه متحد دانشجویی و جبهه دموکراتیک ایران بار دیگر تصریح میکنند که آینده ایران در گرو تقویت جامعه مدنی، صیانت از کرامت انسانی و التزام عملی و بیقیدوشرط به اصول دموکراسی و حقوق بشر است.

📡 Student Message Press

🌐 www.studentmessagepress.com

Editorial Note

Democratic Transition, Institutional Design, and the Strategic Role of the Student Movement in Iran

Scholarly literature on democratic transitions consistently demonstrates that sustainable political change is not merely the result of elite replacement or power redistribution. Rather, it depends on the gradual construction of resilient institutions, the internalisation of democratic norms, and the establishment of a broad-based consensus around fundamental rights and constitutional principles.

Comparative experiences over the past five decades—from Southern Europe to Latin America and parts of Eastern Europe—indicate that successful transitions occur when political actors distinguish between competition for power and commitment to shared democratic rules. Where institutional safeguards, pluralism, and rule-based governance are prioritised, democratic consolidation becomes possible. Where they are neglected, authoritarian relapse often follows.

Within this analytical framework, Iran’s student movement must be understood not as a periodic protest force, but as a structurally significant component of civil society. Historically, student activism in Iran has functioned as a normative engine—articulating discourses of freedom, accountability, and justice at pivotal historical moments. Its strategic importance lies not only in mobilisation capacity, but in its ability to redefine political horizons and ethical expectations within society.

Iran today faces structural crises: erosion of public trust, economic strain, political fragmentation, and institutional stagnation. In such circumstances, the central question is no longer merely “who governs,” but whether democratic infrastructures, protection of civil liberties, and accountable governance will be established.

The joint statement issued by the United Student Front and the Democratic Front of Iran should be analysed within this broader theoretical context. It is not simply an endorsement of a call to action. It represents an institutionalist understanding of democratic transformation, prioritising rights-based discourse, peaceful civic engagement, pluralism, and the rule of law over zero-sum power politics.

Historical evidence from failed transitions demonstrates that personalisation of politics, exclusionary strategies, and the absence of consensus on fundamental rights frequently lead to renewed authoritarianism. Conversely, successful transitions are built upon minimal but firm agreement on universal human rights, equality before the law, freedom of expression, and inclusive participation.

Student Message Press considers the role of an independent media institution to extend beyond reporting events. It carries the responsibility of reinforcing rights-based narratives, promoting institutional thinking, and encouraging civic accountability. The publication of the following statement is consistent with that mission.

The full statement appears below.

Press Release

Joint Statement of the United Student Front and the Democratic Front of Iran

In Support of Student Calls

February 15, 2026

Tehran

The United Student Front and the Democratic Front of Iran hereby formally announce their support for the recent calls issued by Iranian students.

Throughout modern Iranian history, the student movement has remained one of the most dynamic and influential pillars of civil society. At critical junctures, it has articulated demands centred on freedom, justice, accountability, and lawful governance. Accordingly, student demands grounded in fundamental civic rights—including freedom of expression, independent association, peaceful assembly, and civic participation possess full legitimacy.

We emphasise that the pursuit of these demands must remain anchored in democratic principles, adherence to the rule of law, and internationally recognised human rights standards. Strengthening a culture of dialogue, recognising political and social pluralism, and guaranteeing equal rights for all citizens constitute essential prerequisites for any sustainable and just transformation in Iran.

At a time when Iranian society faces complex political, economic, and social challenges, civil and political actors bear the responsibility of supporting lawful and peaceful student demands while avoiding exclusionary, escalatory, or violent approaches. The path toward democratic governance can only be advanced through the strengthening civil institutions, informed civic participation, and guarantees of fundamental freedoms.

Heshmat Tabarzadi, Secretary-General of the Democratic Front of Iran, underscores the necessity of solidarity among civil and political forces in defending fundamental civic rights and reaffirms his support for the lawful and peaceful demands of students. He further emphasises that institutional democracy, equal rights, and unwavering commitment to universal human rights principles are indispensable foundations for a stable, just, and development-oriented future for Iran.

The United Student Front and the Democratic Front of Iran reiterate that Iran’s future depends on the empowerment of civil society, protection of human dignity, and unconditional commitment to democratic principles and human rights.

📡 Student Message Press

🌐 www.studentmessagepress.com